The Great War of 1914-1918 was fought world-wide: in Italy, the Balkans, Russia, Egypt, Arabia and Australasia. It was fought on land, on sea and in the air. Not only were troops engaged but also civilians – from 1915 bombs were dropped onto London from German Zeppelin airships with over 2,000 civilians being killed or injured as a result of such raids. However, most people in Britain today think of the war as being fought more-or-less exclusively on the Western Front and by soldiers in trenches. The poppy and the trench are the two iconic emblems of the War.

Contents

The Great War was fought between two sides known as ‘The Allies’ and ‘The Central Powers’. Britain and her colonies were on the Allied side; Germany was the leading nation on the side of the Central Powers.

The Western Front.

‘The Western Front’ refers to the war fought on land to the west of Germany- in Flanders; the ‘Eastern Front’ was east of Germany- in Russia.

The Western Front was the first location of fighting in the Great War. On 3rd August 1914 German troops crossed the Belgian border, swept aside the small Belgian Army and quickly occupied Brussels. The French and British armies rallied to the aid of the Belgians, met the German advance and prevented the Germans from reaching Paris. Then, in order to hold onto those parts of France and Belgium that Germany still occupied, the German commander ordered his men to dig trenches to provide protection from the advancing French and British troops. When the Allies realised that they could not break through this German defensive line, they too dug trenches. Over the next few months the equally-matched armies tried to outflank each other, continuously adding on to their trenches as they went. Soon trenches had been dug from the North Sea to the Swiss Frontier, about 25,000 miles of trench in all. This line became known as the Western Front.

The territory between the two opposing lines of trenches was called ‘No Man’s Land’. The width of No Man’s Land varied considerably but on average was 230 metres; at Cambrai in Northern France it was 460 metres and at Zonnebeke in Belgium it was 7 metres.

In his memoirs An Adjutant in France, Arthur Behrend, a balloon observer, described what the front- line looked like from the air:

At six hundred feet we were free of most earthly noises, and again I looked down. For the first time I saw the front line as it really was, mile upon mile of it. Now running straight, now turning this way or that in an apparently haphazard and unnecessary curve, now straight again, it stretched roughly north and south till it vanished in both directions. The landscape was alive with the puffs of bursting shells and the green flashes of batteries in action, and the brief glow of some newly-created fire.3

Why trenches?

With the benefit of hindsight putting troops in trenches seems a bizarre and particularly unpleasant idea, but at the time it was a perfectly sound and sensible decision. The trenches were vital to defend the men:

“They had to hide in the mud of the trenches to escape the German bullets. It was a choice of mud or death.”4

Up until this time the conventional way of fighting a war was for the two armies to face each other in the field and shoot. But the tactics of the Napoleonic Wars were not appropriate for the wars of the twentieth century. In the intervening 100 years there had been a massive technical improvement in the capability of weapons. A musket of 1814 could fire three shots a minute at a range of 100 metres; in 1914 a bolt-action rifle fired ten rounds a minute at a range of 500 metres. In 1814 a cannon fired solid shot once a minute to a range of 1,000 metres in 1914 a breech loading field gun fired shrapnel ten times a minute to a range of 5,000 metres.5 These developments in offensive weaponry had not been matched by improvements in defensive armour and so soldiers were more likely to get killed in battle. To avoid their army getting annihilated in northern France the Germans had to hide their men. The terrain in northern France and Belgium is flat and agricultural and the number of troops needing protection was huge, (over two million men fought in the Battle of the Marne in August 1914), so the suit.

The idea of digging trenches was not brand new – it had been used by the British in the Boer War (1899-1902) and in the battle between Russia and Japan over Korea (1904 -1905). What was different this time was the enormous scale of the trench network.

Trenches had proved very easy to defend and very hard to attack.

“The principal aim of field fortification or entrenchment is to enable the soldier to use his weapons with greatest effect, the second to protect him against the adversary’s fire.. thus reducing losses and increasing the power of resistance in any part of the theatre of operations or field of battle.”6

Constructing a Trench.

J. B. Priestley, in the Duke of Wellington’s West Riding Regiment, wrote to his father, 26th October, 1915:

We have been digging trenches since we have been here; it is very hard work, as the soil is extremely heavy, the heaviest clay I have ever dug and I’ve as much experience in digging as most navvies. You may gather the speed we work when a man has to do a ‘task’ – 6 ft long, 4 ft broad and 2 ft 6 ins deep in an afternoon. Yesterday afternoon I had got right down to the bottom of the trench, and consequently every blooming shovelful of clay I got I had to throw a height of 12 ft to get it out of the back and over the parapet.7

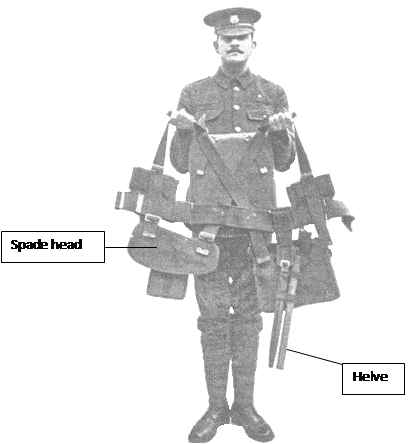

All British non-commissioned ranks carried an ‘entrenching tool: 1908 pattern’ as part of their personal equipment. This was a metal head with a wooden handle. The head was a spade at one end and a pick at the other. The handle was called a ‘helve’.

When not in use the tool broke down into two parts with the metal head being stowed in a special canvas web carrying case and the helve carried beside the bayonet, threaded through a webbing carrier.

Battle of Langemarck. A large number of French and British troops resting after digging trenches on Pilckem Ridge, 19th August 1917. IWM

Defence of Hinges Ridge. Men of the 51st Division digging in near Locon, 10 April 1918. IWM

There were two main ways to dig a trench. Firstly there was entrenchment, which was the faster method, allowing many soldiers equipped with their shovels and picks to dig a large portion of trench at once. The soldiers stood in a line on the surface and dug. However, this left the diggers exposed to all of the dangers that the trenches were supposed to protect against. So entrenchment had to take place either in a rear area where diggers were not as vulnerable, or at night. British guidelines for trench construction state that it took 450 men approximately 6 hours to dig 275 yards of a front-line trench (approx. 7 feet deep, 6 feet wide) a night.

The other option was sapping, where a trench was extended by digging at the end face. It was a much safer option, but took more time, as only one or two men could fit in the area to dig. The men hid in a small hole called a scrape and gradually extended it without exposing themselves to the enemy. Tunnelling was similar to sapping but an overhead section was left in place until the trench was complete.

Trench design varied depending on the local conditions. In the area of the River Somme on the Western Front, the ground is chalky and was easily dug but the trench sides crumbled in the rain, so had to be built up (‘revetted’) with wood, sandbags, chicken wire or any other suitable material. At Ypres, the ground is naturally boggy and the water table very high, so trenches were not really dug, more built up using sandbags and wood (these were called ‘box trenches’).

British troops taking up timber for a trench support at Ploegsteert, March 1917. IWM

Troops of the Australian 2nd Division in a box trench near the Bridoux Salient in June 1916. IWM

The floor of the trench had to slope to a gutter which ran into soak- away pits lined with stones to prevent the trench getting flooded and wooden planking, referred to as duckboard, was put on the floor to prevent men from walking in mud.

Some kind of floor should be provided for the trenches. The simplest and best are made the following way: Take two seven-inch boards about ten feet in length, nail them together to make a fourteen-inch plank, and then cover the whole with fairly fine chicken wire. Place these boards on the ground with the side on which the wires are joined downwards. They keep the feet from slipping, are easily cleaned by being upended when they are dry, and allow the space under them to be reached easily to pick up scraps of food, etc. There is nothing more heart breaking than having to pursue your weary course for miles, sometimes, up trenches with slippery sides and sloping, wet, treacherous bottoms.10

View of front line trench showing sandbag, dugouts, duck board track running through, 19th October, 1915. IWM

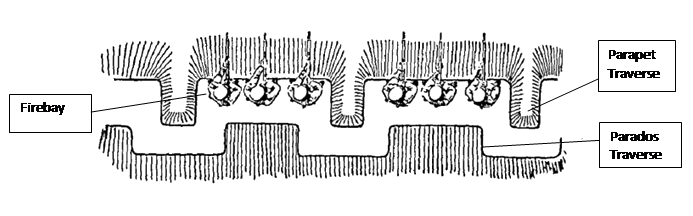

The trenches were built in long straight lines but the paths inside were laid out as a zig-zag; this was to prevent an enemy who had entered the trench from firing along its whole length. The alcoves were called firebays and the buttresses were called traverses.

Trenches do not consist of one straight line, but what may be described as a succession of little rooms, about twenty feet long, seven feet deep and three feet broad. They are seldom roofed over. Each little room is connected to the ones on either side by a trench that runs behind the four-feet square traverse that is of solid earth and which serves the purpose of localising the effect of shells, bombs, etc.12

Indian soldiers, fighting for the British, in a trench – showing the traverses.13

Dimensions vary up and down the line. Sometimes according to the lay of the land, sometimes according to the opinions, whims or fancies of the regiments making them, but the following dimensions should be kept in mind, and it will be found that they show the average of the whole general line of the Western Front. Firebays generally are from 12 to 18 feet long (defendable by 4 to 6 men but accommodating 8 to 12 when necessary) plus a two foot covered sentry box recessed into the traverse and giving room for one more man; this depending entirely on the energy and initiative of the men occupying the station.

Every traverse averages 9’ by 9’ which includes a fairly liberal allowance for wear and tear, and is the minimum allowance for stopping enfilade fire and localising fire.. Three feet may be taken as the maximum width at the bottom of the trench, that is 11/2 ‘ for traffic and 11/2 ‘ for those firing, with a slope to the sides of 10 to 15 degrees from perpendicular, thus lessening the tendency of the walls, whether revetted or otherwise, to slide in.

The depth of the trenches also varies, for the same reasons that cause the width to vary. Recesses should also be dug at various and favourable places for the storing of ammunition and bombs.14

Captain H. L. Oakley’s cut-out for The Bystander magazine on 8 March 1916.15

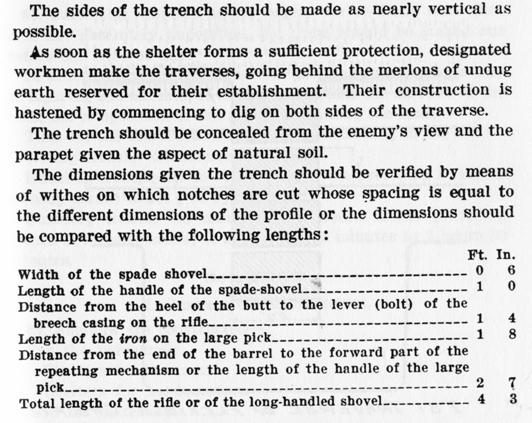

French Army Instruction Manual IWM

French and British troops digging trenches together on Pilckem Ridge, 19th August 1917. IWM

Types of Trench.

Contrary to common belief not all the men in trenches were on the front line. The trench system was built as a network with the front line trenches, known as ‘fire trenches’ connected to ‘support trenches’ in rows about 90 metres behind and then to ‘reserve trenches’ about another 200 metres behind that. Connecting the three rows together were ‘communications trenches’. Soldiers and supplies moved backwards and forwards along the communications trenches.

The front line is, of course, the most important one, and the greatest amount of work has to be done there. But support and reserve lines as well must be constructed and many communicating trenches. Support lines were usually dug at a distance of thirty to eighty yards from the firing line. In them we kept a few men to be used in case of emergency. This line was an exact duplicate of the front line and was intended to be used in case we were pushed back. The reserve line was about five to eight hundred yards back from the front line and was not brought to any great degree of completion. Interspersed between these three lines were many redoubts, or especially strong points containing machine guns, etc., whose defenders were expected to hold on to the very last and take advantage of their more secure position to make the attacker pay dearly for his advance. All these lines had to be linked up by communicating trenches, which started about a mile in the rear of the front line and went up in zigzag lines to the latter position, crossing the other trenches on their way. These communicating trenches are used for the purposes of bringing up troops and supplies etc, and for taking to the rear the men that have been wounded. It is usually arranged to have some of these trenches “Up” and some of them “Down” roads. Each line of trenches (except of course the ‘communicating’) contain dugout for the use of the troops that hold them. The distance between the communicating trenches varies from twenty-five yards to three or four hundred according to the state of perfection of the trench system.17

Flanders. Digging reserve trenches in a hop field near Meteren by the edge of a road. Note tapes marking out the bays and traverses. 13 April 1918. IWM

The general pattern for trench routine was four days in the frontline fire trench, then four days in the reserve trench and finally four at rest behind the lines in a billet, although this system varied enormously depending on local conditions, the weather and the availability of enough reserve troops to be able to rotate them in this way. In reserve, men had to be ready to reinforce the line at very short notice.

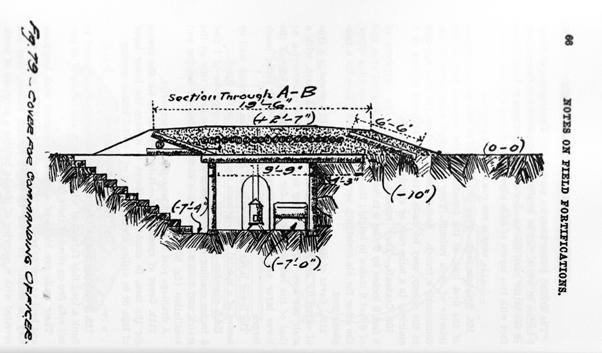

Positioned along the support trenches were dug outs used as officer accommodation and command posts. These were about 4.5 metres deep and lined with timber with wooden ceilings. Often they had telephones in them.

Cover for a commanding officer. French Army Manual IWM

Conducting a Battle in a Shell Proof Dugout. Photo by Frank Hurley 1917

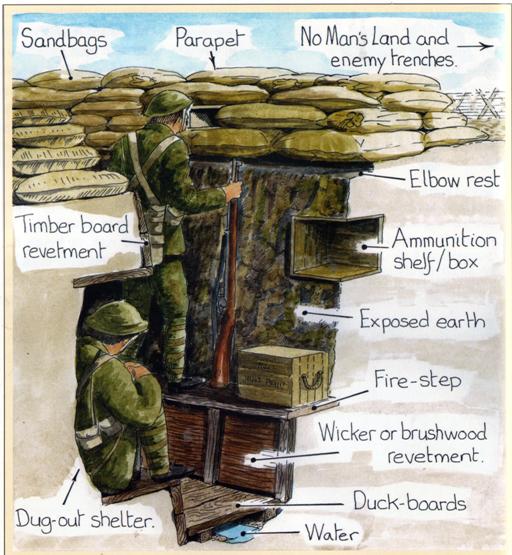

Fire Trenches

These were the front line trenches normally shown in films.

The trenches had to be deep enough for a soldier to stand up and walk without being seen and wide enough for two men to pass each other. Ideally they were 3 metres (10 feet) deep and 2 metres (6 feet) wide. The earth that was dug out of the trench put into sandbags and piled up like bricks at the front ( the parapet) and rear of the trench (the parados) to protect the soldiers from shrapnel.

On the side walls of the trench steps known as ‘fire steps’ were dug out so that the soldiers could stand on them when they wanted to shoot the enemy. They shot their rifles either over the top or out of loopholes – gaps left in the wall of sandbags. Higher up the walls there were small recesses for storing ammunition and these could also serve as steps when the soldiers were going over the top.

Manual of Field Engineering Chapter V. Earthworks 1914

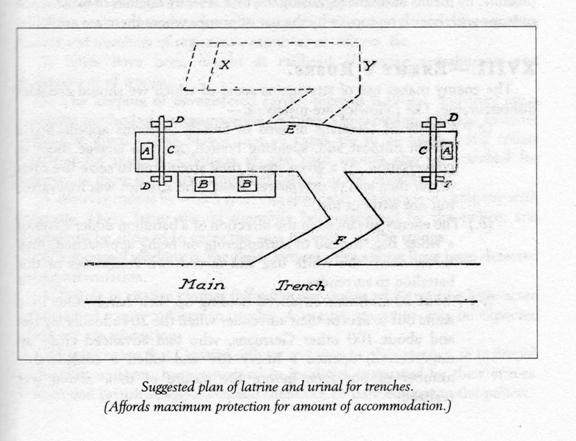

Latrines

The trenches had toilets called latrines. These were built into a small side trench off the main fire trench. They contained biscuit tins with seats- for faeces, and biscuit tins without seats for urine. The tins were emptied every night and the smell was kept down by the use of chloride of lime.

Sleeping

There are plenty of photographs of soldiers asleep in trenches but soldiers were supposed to sleep in dugouts.

In each trench there must be dugouts for the men to sleep in. The first ones that are made will be very primitive, and will be very much like a fireplace in a room- simply excavations in the back wall of the trench almost on a level with the bottom of it. At first they used to be dug in the front of the trench, but this practice was discontinued as it was found to weaken the power of resistance of the very important parapet. In the course of time more labour can be expended upon the dugouts, and it will be found advisable to construct them of uniform size, six feet long by four feet wide by four feet high. By having them uniform we give the engineers a chance to make frames that can be used to support the roof and the sides and bring them well from the rear to construct the dugouts. These dimensions do not make a very commodious home for four men, but never more than three of a section (of four) are off duty at the same time, and besides there is considerable danger in having large dug-outs, as they present a correspondingly larger target for the guns. .. The entrance to the dugouts must be kept as small as possible so as to protect the occupants from shells that fall outside.20

Lieutenant Rees of the Durham Light Infantry described his dugout in a letter in December 1915:

‘I am as warm as a pie in my dug out which I share with two others, there is only just room to creep in but it is not much used as we have not much time to sleep except during part of the day’22

Conditions in dugouts varied according to the rank of the soldiers and the condition of the trench. Officers had dugouts constructed with a corrugated iron roof, wooden beams and sand bags, Second Lieutenant George Brabazon Stafford of the Durham Light Infantry kept a photograph album and sketch book of his experiences and drew an annotated sketch of his dug out in Canada Trench, near Arras in France, September 1917.

Advertisement in Musketry Imperial Army Series John Murray 1915

In front of the fire trench was a look-out post called a sap, then rows of barbed wire fencing, then No Man’s Land.

Major Oliver Lyttelton, letter home 21st February, 1915:

Things are quiet, a little shelling now and again, but not much. We lie very low when it is on, right under the bank or in a dugout. All the men have little fires in this and keep decently warm whilst they sleep, which they do in amazing positions. ‘Make way’ is the commonest remark as we go along the lines, with elbows rubbing the sides…You see in front of you a greyish clay bank to about two feet above your head, to your right and left about six men before a traverse stops your view…

The night I was in, we completed a line of trenches gaining connection with the French (we are the extreme right of the British position) digging quite openly above ground without casualties except one engineer hit in the thigh. This, mark you, within 150 yards of the enemy on only a darkish night. The Royal Engineers are wonderful; they put up wire about 11.30 when the moon was quite bright, bang in front of a new sap trench, without loss. Amazing. This digging is ticklish work but losses are very small generally at it.25

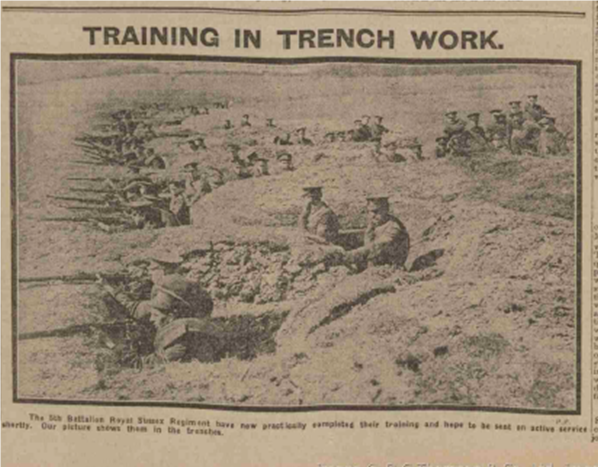

Training Trenches

British soldiers were not sent to the Western Front as raw amateurs. Archaeological evidence from all parts of Britain shows that the army tried to provide soldiers with realistic training in the form of elaborate training trenches, instructional models and full-size mock-ups of the German lines. Many sites have been revealed by aerial photography or old plans and photographs. Others are now overgrown in woodland or heathland but their purpose can be identified from the distinctive zig zag of the front lines. These sites are being resurrected in commemoration of the centenary of the outbreak of war and so far 20 sites have been documented.

For example two sets of opposing trench systems, with a no man’s land between them, have been found beneath heathland at the Ministry of Defence’s Browndown site in Gosport. Each trench system had a 200m long (660ft) front line, supply trenches and dug outs and the area covers 500m (1,640ft) by 500m.27

Soldiers march along the front line trench of a newly discovered First World War mock battlefield in Gosport, Hampshire. Photograph: Ben Mitchell/PA

Again, at Clipstone in Nottinghamshire the remains of a huge army camp have been found. Clipstone Heath was used as the training ground; rifle and pistol ranges were constructed and a large network of trenches, straight, curved, right-angled and zig-zag, were dug across the heath as far as Mansfield.28

In Ireland a full practice trench system and dugouts, plus an old 600-metre gallery range has been discovered at Ballykinler. These are thought to have been originally used by the 36th Ulster Division in preparation for the Battle of the Somme.29

In Scotland a network of trenches at Dreghorn Woods, Colinton, has been discovered and preserved by Edinburgh City Council. The 16th Battalion, The Royal Scots dug the trenches in land which was open countryside at the time – before they made their way to the front.30

At Berkhampstead in Hertfordshire over 13 miles of training trenches were dug on the Common of which just 500 metres remain. The trenches were used by more than 14,000 troops from the Inns of Court Officers’ Training Corps, nicknamed ‘The Devils Own,who were stationed in Berkhamsted right through the Great War of 1914-18. They dug the trenches mainly as a rehearsal for the forthcoming experience of real trench warfare on the Western Front and partly as fitness training.

Here are some suggestions for how what the training could involve:

Men should be taught to dig trenches in broad daylight at first and then when they have learnt the knack, they should be set to dig them at night. From time ti time during their training they should be made to return – preferably to the same sections of the trenches- to improve them and maintain them. An excellent scheme is to arrange competitions among the men to spur them on to invent ingenious devices for protecting themselves and their fellows during their occupation of them. At certain times they should also be made to spend a night and then several nights there, going through the regular routine of sentry duty, stand to arms, etc., just as they will have to in real warfare. Another scheme is to choose opposing sides with trenches within easy reach, say twenty –five yards apart. Arrange a three-day tour of the trenches, and let each side attempt to surprise the other. Umpires can be stationed in no Man’s Land to decide as to the relative merits of the two sides. At certain times, additional interest can be given to the conflict by some harmless missiles such as sand-bags (without the sand!) rolled up and made into a ball excellent practice in bomb throwing.32

The 5th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment have now practically completed their training and hope to be on active service shortly. Our picture shows them in the trenches33. Location unknown.

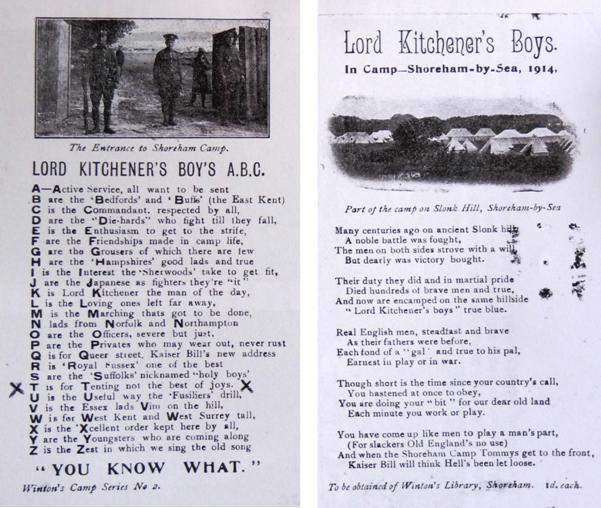

Shoreham Camp

One location with training trenches was Shoreham Camp.

In autumn 1914 Shoreham was chosen as the site for the training camp for Kitchener’s Third New Army. Horatio Kitchener was Secretary of State for War and, appreciating that the war was likely to be a difficult and long drawn out affair, he saw the need for a large and well trained British army. He launched a recruiting campaign for volunteers to sign up. The first 100,000 men enlisted became Kitchener’s First New Army (K1 ; this figure was achieved in two weeks. Then came K2 and K3. Almost 2.5 million men volunteered for Kitchener’s Army.So many men had been recruited that the army was not able to house them all and new make-shift training centres had to be constructed- Shoreham was one of these.

Who can forget that Saturday afternoon when a train steamed into Shoreham bearing some hundreds of men- part of that great army which will ever be known as Kitchener’s Boys?

Train after train followed till far into the evening. In drenching rain thousands of men marched by way of Buckingham Road to the camp – a camp in name only, for there all was in a state of chaos. Stores had gone astray, provisions were lacking and much hardship was experienced.

The following days witnessed the arrival of thousands more, and the daily routine of camp-life began in earnest and with it there arose something of a holiday-making atmosphere, and our somewhat dull little town took on a new garb as its streets were thronged with these light-heated warriors in the making.34

The camp was erected on peaceful open farm land and the area known as Buckingham Park. At first the men lived in tents but during the early months of 1915 a huge town of huts was constructed; complete with a canteen, chapel, post office and social clubs.

A postcard sold at the camp showing neat rows of tents.

As the war lingered on more troops were sent to Shoreham and the camp became a base for Canadian troops as well as British. Shoreham rapidly expanded into two distinct camps: Mill Hill for recruits and Slonk Hill for learning advanced soldiering.

At first the recruits had to practice rifle firing indoors with pretend bullets using in the ground floor of Marlipins Museum and two large greenhouses at East Worthing on the sea front. Later an outdoor rifle range was set up at distances of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 yards on the open downland above the camp.

After seven weeks when the initial training had been completed further instruction in field craft, route marches, the use of machine guns and trench mortars took place. The area above Buckingham Park and Slonk Hill was transformed to create a realistic battleground where trenches were dug and barbed wire laid before them.35

Trenching Party at Shoreham Camp by Marshall Keene, Portland Road, Hove.

Two soldiers who trained at Shoreham and who recorded their experiences were a pair of brothers; 15176 Private Edmund Leonard (“Ned”) Goodchild, and 15103 Private Arthur Goodchild, of the 9th Battalion Suffolk Regiment. The original letters can be seen on the Shoreham Fort website. Here are two extracts:

A Coy 9th

Sffk Regt

Shoreham by Sea Sussex

13 November 1914

My Dear Mother,

We have not been for a Battalion route march lately, but go for a short march every morning before breakfast, and back again before it’s properly light. We always have to be on parade at 6.30 and sometimes before. We are called at 5.30 and should have our blankets rolled up by 6 o’clock and we must not be a minute late on parade. I have not been late since I have had my watch. They have given us two blacking brushes and a tin of dubbin each. We have to keep our boots clean and keep our clothes clean and our tents have to be kept perfectly clean. There must not be a piece of paper laying about and the boards of our tents have to be washed every morning. We went trench digging last Wednesday and have been again this morning. It take a long time to dig a trench here, for when we get down a foot we come to solid chalk, and we have to pick it up. We go about three miles inland to dig the trenches, and when we got there this morning it rained pouring. We worked for half an hour and then started back but we didn’t take any harm for most of us had brought our coats. I had got mine. There are more sheep further inland and they are quite tame. They are the same breed Colonel Thomson had last year, and some of them have got bells on. That chap I told you about who stand 6ft 4inches hurt himself yesterday. We have to make short rushes about the hills with our rifles and we were running down one of the steep slopes and he stumbled and fell and hurt his thigh and he is in the hospital now. I think the war is going on very well for our side, but it won’t be over yet, they still want more recruits, and if the men won’t enlist they will make it compulsory. If they won’t go on their own they ought to be forced, the country wants them. I will close now. I hope you are all as well as I am, with love to you all, from your affectionate

Arthur

C Coy 9th Batt Suff Regt

Shoreham by Sea

30 March 1915

Dear Mother,

I have been a bit uneasy this last three or four days with the tooth ache, but it is alright I am glad to say. I went down to Shoreham and had it out. It was a bit of a pinch but I did not mind that so long as I got rid of it. We have had a medical examination, just like enlisting again, the army dentist is going to do something to my front teeth to get them regular. He is removing some chaps’ teeth that have got very bad ones, and putting false teeth in rather than discharge them. He says it’s a pity my teeth [are] so unregular in front, as I have got some very good back ones. He is going to make them a bit more comfortable for me. He is a very nice chap and takes a lot of interest in his work. We have to go trenching at night now, I should go tonight but I am in the sergeant’s mess today. It suits me better than trenching in the cold wind, as I have just had that tooth out. They are learning us to make bridges now. We get on very well at that and our officers are very pleased with what we have done. I like it. It just suits me, and I do all I can to help them as it is very interesting, the cunning way they have of going to work. It takes a good man to know how to tie all the knots wanted for that job. In another week or two we are going to learn barbed wire entanglements. I shall stick to that as much as I can, there might be a chance to transfer into Royal Engineers. C Company was the first one to learn it, as it is the forwardest in the other drills. Dear Mother, now I will close. With love to all from your affectionate son

Ned36

Ned was killed at Ypres in 1917.

—Hilary Greenwood

May 2014

Bibliography

- New York Times April 2 1915

- Evening Telegraph – Monday 12 April 1915

- Trench Fortifications 1914-1918 A Reference Manual. Imperial War Museum

- Bull, Stephen ed. An Officers Manual of the Western Front 1914-1918 Conway 2008

- Bull, Stephen. World War 1 Trench warfare(1) Osprey 2009

- Cheal, Henry The Story of Shoreham Hoves, Combridges 1921

- Dane, Edmund. Trench Warfare. United Newspapers 1915

- Parrott, James Edward. The Childrens’ Story of the War, Volume 3 From the First Battle of Ypres to the End of the Year 1914 Nelson 1916

- Smith, J.S. Trench Warfare: A Manual for Officers and Men Dutton & Co 1917

- Solano, E. John. Field Entrenchments: spadework for riflemen Murray 1916

- Vickers, Captain Leslie. Training for Trenches George Doran 1917

- Yorke, Tevor. The Trench Countryside books 2014

- http://blog.maryevans.com/

- www.diggerhistory.info/pages-equip/web-1908.htm

- www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk/

- http://education.mnhs.org/

- http://goodchildsdotorg.files.wordpress.com

- http://www.greatwar.nl

- www.gwpda.org

- http://historicalphotosdaily.blogspot.co.uk/search/label/WW1%20Trenches

- www.iwm.org.uk/collections

- www.shorehambysea.com

- www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/FWW.htm

For more on Shoreham Camp see:

- http://www.shorehambysea.com/shoreham-historical-articles/world-war-i/slonk-hill-military-camp- presentation/shoreham-history-photo-collection/slonk-hill-military-camp-photos.html

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o90fpG62eQw

Footnotes

- http://education.mnhs.org/ ⏎

- http://www.greatwar.nl ⏎

- Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk ⏎

- Aitken, Max New York Times April 2 1915 ⏎

- Bull, Stephen. World War 1 Trench Warfare Osprey 2009 ⏎

- Solano, E. John Field Entrenchments: spadework for riflemen Murray 1916 ⏎

- Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk ⏎

- www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30013895 ⏎

- http://www.diggerhistory.info/pages-equip/web-1908.htm ⏎

- Vickers Captain Leslie. Training for Trenches George Doran 1917 ⏎

- Dane, Edmund. Trench Warfare. United Newspapers 1915 ⏎

- Vickers Captain Leslie. Training for Trenches George Doran 1917 ⏎

- Dane, Edmund Trench Warfare. United Newspapers 1915 ⏎

- Smith, J.S. Trench Warfare: A Manual for Officers and Men. Dutton & Co 1912 ⏎

- Mary Evans Picture Library ⏎

- Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk ⏎

- Vickers Captain Leslie. Training for Trenches George Doran 1917 ⏎

- Yorke, Tevor. The Trench Countryside books 2014 ⏎

- Notes from the Front part 3 Stationary service Pamphlet 1915 ⏎

- Vickers Captain Leslie. Training for Trenches George Doran 1917 ⏎

- www.gwpda.org ⏎

- www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk ⏎

- www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk ⏎

- Parrott, James Edward. The Childrens’ Story of the War, Volume 3 From the First Battle of Ypres to the End of the Year 1914 Nelson 1916 ⏎

- Spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk ⏎

- Manual of Field Engineering 1914 Chapter V Earthworks ⏎

- www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-hampshire-26471922 ⏎

- http://sherwoodforestvisitor.com/2012/10/18/sherwood-pines-clipstone-heath-forest-war-time-role/ ⏎

- www.gov.uk/government/news/first-world-war-trenches-uncovered-at-ballykinler ⏎

- http://www.scotsman.com/news/scotland/top-stories/edinburgh-first-world-war-trench-survey-begins ⏎

- http://www.hampsteadpals.com/in-search-of-the-devils-own-trenches-on-berkhamsted-common ⏎

- Vickers Captain Leslie. Training for Trenches George Doran 1917 ⏎

- Evening Telegraph – Monday 12 April 1915 ⏎

- Cheal, Henry The Story of Shoreham Hoves, Combridges 1921 ⏎

- http://www.shorehambysea.com ⏎

- http://goodchildsdotorg.files.wordpress.com ⏎

- Cheal, Henry The Story of Shoreham Hoves, Combridges 1921 ⏎