The Dieppe Raid, also known as Operation Jubilee, took place on 19 August 1942. Allied forces based in Sussex and Hampshire crossed the Channel and attacked the French port of Dieppe, which at that time was occupied by the Nazis.

The Second World War began on September 3rd 1939 when Britain and France declared was on Germany in response to the invasion of Poland by Nazi troops. In the early days of the War the Germans were highly successful; they rapidly defeated Norway, Denmark, Holland and Belgium. British forces stationed in Belgium had to be evacuated from Dunkirk at the end of May 1940.

Although Dunkirk is regarded as a huge British triumph with the flotilla of “Little Ships” coming to the rescue, 3,500 British soldiers were killed and 13,053 were injured in the process. All the heavy equipment, including 445 tanks, was abandoned. Six British and three French destroyers were sunk, along with nine other major vessels. In addition, 19 destroyers were damaged.

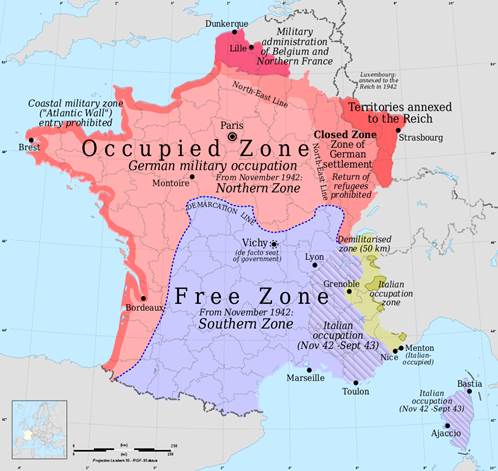

On 5th June 1940 the German army broke through the French defences along the Belgian border and two days later they reached Paris. The French government fled to the south-west of France and on 22nd June 1940 the new French President, Marshall Pétain signed an armistice with the Nazis. By this time the Germans had occupied the whole length of the Channel coast, including Dieppe.

After the swift defeat of Northern Europe and France, Hitler became confident of victory in an attack on Britain, and on 16 July 1940 Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 16, setting in motion preparations for a landing on the South Coast. He prefaced the order by stating:

As England, in spite of her hopeless military situation, still shows no signs of willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare, and if necessary, to carry out, a landing operation against her. The aim of this operation is to eliminate the English Motherland as a base from which the war against Germany can be continued, and, if necessary, to occupy the country completely….The landing operation must be a surprise crossing on a broad front extending approximately from Ramsgate to a point west of the Isle of Wight

The Canadians

The British government felt it was essential to protect the South Coast from possible invasion and realised this would take considerable manpower. Reinforcements were needed from the Commonwealth – and Canada came to the rescue.

The first Canadians to arrive came in December 1939- the 1st Canadian Infantry Division led by Major-General A.G.L. McNaughton – and by February 1940 there were over 23,000 Canadian soldiers in Britain, most of them based in Aldershot. After the disaster in Dunkirk the Canadian war effort was stepped up and in June 1941 the 1st Army Tank Brigade came to England followed by the 3rd Infantry Division and the 5th Armoured Division.

In the summer of 1941 the Canadians were given the task of defending the Sussex coast from Newhaven to Worthing as part of the British South Eastern Command.

The 1st Canadian Army took over the Devil’s Dyke Hotel as its headquarters and much of the South Downs was requisitioned as an intensive training area. Barbed wire entanglements replaced fences, roads were closed and Howitzer guns were parked in lay-bys. Check points were everywhere, with barriers blocking the roads and a pass often needed by locals. Together with British troops, the Canadians engaged in a series of major exercises, and the screech and clatter of tanks and the pounding of heavy artillery regularly shattered the tranquillity of the countryside.3

A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment training on a beach near Seaford, Sussex, in July 1942.4

A Churchill Mark I of the Calgary Regiment training on a beach near Seaford, Sussex, in July 1942.4

The Canadian soldiers were billeted around Sussex and on the whole were popular with the locals.

In Littlehampton their main residence was the Southlands Hotel and their NAAFI was the Bungalow Cafe in Beach Road.

By 1941, in addition to airmen, the district was inundated with a variety of service men. Empty houses and other buildings had been commandeered by the Forces and many householders had soldiers billeted, compulsorily, with them.

Among the troops based in the area during 1941 were the Royal Artillery, some manning the guns on the Green and stationed at the Beach Hotel and Surrey House; the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry; The Royal Canadian Artillery ( some stationed at the Broadmark Hotel); the Royal Regiment of Canada, which had its HQ in Arundel Park and a Littlehampton HQ at ‘Edenmore’ Fitzalan Road, with some of its men stationed at the Golf Club and Roland House in East Street (now Ormsby House); the Royal Canadian Engineers Tunnelling Unit, based at Ford Aerodrome; the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps and the Royal Canadian Medical Corps ( both based at Rosemead School in East Street) ; the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps at Dorset House School in East Street; the Canadian Light Infantry and the Royal Army Medical Corps at the Carpenter’s Convalescent Home; the 48th Highlanders of Canada, some stationed at the old Isolation Hospital in Mill Lane, Toddington. One Canadian unit had its headquarters at Aukland, the Convent School at the top of Norfolk Road and this later became the base of the Royal Army Service Corps. Another Canadian HQ was at St Nicholas School in Fitzalan Road where the Canadian Military Police were based. Men of the Naval Patrol Service also had a base here.5

Here are some reminiscences from local residents:

Rapid moves to safeguard the South Coast were hurriedly made and several army divisions were placed in strategic positions. Court Wick Farm was more or less taken over by the 1st Canadian Division. They immediately erected a strong barbed wire fence around the perimeter of the farmhouse, cottages and farm buildings. We could only leave or enter our home by showing a W.D. pass. The Canadians very quickly dug large underground headquarters where they were safe from all enemy bombs or guns.6

In the town all the large houses and all the houses along the sea front were taken over by the American and Canadian soldiers. All this was exciting for us kids, as we could get some of their chocolates and chewing gum!7

My mother told them they were to feel free to come into our house whenever they wished, for a cup of tea and relax and make it their home, which several of them did. I got to know them. They would come in with huge comics so that we could follow the exploits of Dick Tracy. They would also give us sweets, which, of course, were on ration too, and there were the cards from packets of cigarettes, showing aircraft silhouettes.8

One Summer Evening the French Canadians came to the village (Angmering) and set up their camps under trees around the fields. There was some excitement I seem to remember because believe it or not they had a real BLACK man with them I doubt that any villagers had even seen a Black man at that time. He was huge giant of a man, but a real gentle giant. He was the cook for the soldiers. We children collected their bread from the local bakery for him and in return he saved us the food scraps to feed to our rabbits and chicken.9

Canadian soldiers lending a hand on an English farm, June 194210

Canadian soldiers lending a hand on an English farm, June 194210

Canadians and the Dieppe Raid

Apparently, the Canadian troops got bored with footling around on the South Downs and wanted some real action- or at least that was the view expressed by Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada, when he visited Britain in September 1941. At a speech at the Mansion House given in Mr King’s honour on September 4th 1941, Winston Churchill said he fully understood:

You have seen your gallant Canadian Corps and other troops who are here. We have felt very much for them that they have not yet had a chance of coming to close quarters with the enemy. It is not their fault; it is not our fault; but there they stand, and there they have stood through the whole of the critical period of the last fifteen months at the very point where they would be the first to be hurled into a counterstroke against an invader.

No greater service can be rendered to this country: no more important military duty can be performed by any troops in all the Allies. It seems to me that although they may have felt envious that Australian, New Zealand and South African troops have been in action, the part they have played in bringing about the final result is second to none.

The first opportunity to send the Canadians into battle came when the Combined Operations Headquarters decided to launch an attack on Dieppe. Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten was the architect of the raid.

Object

- Intelligence reports indicate that Dieppe is not heavily defended and that the beaches in the vicinity are suitable for landing Infantry, and Armoured Fighting Vehicles at some. It is also reported that there are forty invasion barges in the harbour.

- It is therefore proposed to carry out a raid with the following objectives:–

- destroying enemy defences in the vicinity of Dieppe;

- destroying the aerodrome installations at St. Aubin;

- destroying R.D.F. (radar) Stations, power stations, dock and rail facilities and petrol dumps in the vicinity;

- removing invasion barges for our own use;

- removal of secret documents from the Divisional Headquarters at Arques-la-Bataille (a castle)

- to capture prisoners.

Intention

- A force of infantry, Air-bone troops and Armoured Fighting Vehicles will land in the area of Dieppe to seize the town and vicinity. This area will be held during daylight while the tasks are carried out. The force will then re-embark.

- The operation will be supported by fighter aircraft and bomber action. 11

In order to train for the raid on Dieppe the Canadian troops were sent to the Isle of Wight, an exercise known as Operation Rutter. A dress rehearsal for the raid, took place on 11th-12th June near Bridport, Dorset, on a stretch of coast resembling the Dieppe area. The result was far from satisfactory; units were landed miles from the proper beaches, and the tank landing craft arrived over an hour late. In these circumstances, Lord Louis Mountbatten decided that further rehearsal was essential. The troops remained in the Isle of Wight, and the second exercise was carried out at Bridport on 22nd-24th June. The results were much more acceptable.12

However, the concentration of shipping about the Isle of Wight had not escaped the notice of the Germans and on the morning of the 7th July four aircraft hit the landing ships, Princess Astrid and Princess Josephine Charlotte.

On 8th July the raid was cancelled; the bitterly disappointed soldiers were disembarked and the force which had spent so long in the Isle of Wight was returned to the mainland and dispersed.

A week later the Raid was back on – but this time the troops were split up and set sail from five different ports so there would not be an obvious flotilla.

The final planning for the operation was carried out at Lancing College (HMS King Alfred L) where the Canadian army and navy commanders Lieutenant Colonel D. Menard and Lieutenant Commander J. H. Datham arranged the embarkation.13

- From Southampton: The South Saskatchewans and the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry along with part of the Essex Scottish Regiment and No. 4 Commando

- From Portsmouth: The Royal Regiment of Canada and the remainder of the Essex Scottish Regiment, part of the 14th Tank Battalion (Calgary Tanks) along with the Royal Marine A Commando

- From Newhaven: the Cameron Highlanders, part of the 14th Tank Battalion (Calgary Tanks) No. 3 Commando

- From Shoreham Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal14

Gosport was the fifth port used but no records are available so far. Littlehampton’s role has not been discovered.

In May 1942, Mountbatten had ordered the construction of 11 purpose built hards to serve landing craft and ships that would support his Commando operations on the European coast. These 11 were all constructed in the Portsmouth Command area (between Portland and Newhaven) and complete by July. These included six hards in the Solent.15

The conversion of numerous Thames barges into small landing craft was undertaken at Shoreham and Poole Harbour by Mackley &Co. The barges were fitted with engines, steering and landing ramps.

The Operation was launched from the various south coast ports, and each flotilla’s departure was timed so the fleet would arrive off the coast at Dieppe at the correct moment. Most left in darkness, but the ships from Southampton had to leave while it was still daylight because of the longer journey and so were disguised as a coastal convoy to avoid detection.

Canadian soldiers lending a hand on an English farm, June 194216

Canadian soldiers lending a hand on an English farm, June 194216

Ron Beal from the Royal Regiment based in Littlehampton recalled the raid

I think we honestly believed that we were going to be the storm troops for the second front. The weekend before, we were stationed in Littlehampton on the south coast [of England] and the day before, on the Saturday, at 3:00 in the afternoon, just as the children were coming out of the theatres, German fighters came and strafed right down the high street. And quite a few children were killed. They dropped a few bombs and destroyed a few houses. Some people were killed, some people trapped. We immediately went to work and started to dig people out of the rubble. And we were really cheesed off and we wanted to get at them. And we had our chance. We didn’t know that just a few days later, we’d be going on the boats and mounting the raid. But we were ready. We’d had good training, we were fit, we were angry, we wanted to get at them, and I think our anger was justified. And we wanted to get back as good as they gave to those kids and better.17

The Royal Regiment, although based at Littlehampton, actually embarked from Portsmouth.

We moved to Littlehampton on the Channel coast. There we relieved the First Canadian Division, Forty-Eighth Highlanders, and settled in to what we thought would be a great place to be billeted.

On the first Sunday there, two German F.W.190s came in very low over the Channel and dropped five hundred-pound bombs, one a direct hit on a cinema that killed and injured a lot of innocent children. The second plane dropped its bomb on a huge pyramid shaped cement obstacle that was on the coast as part of a yank barrier.

This explosion blew several of us back into the doorway of our billets, breaking all the windows on the main street.

This all seemed very strange. First, they bombed the Royal’s two ships off the Isle of Wight and now they were after us in Littlehampton. It looked like the Germans knew something was in the wind.

Several of us had contracted trench mouth (infection of the gums) while on the Isle of Wight. This was a result of washing out our mess tins in filthy water. We received treatment for the trench mouth from a Canadian dentist. While returning from our third treatment for this disease, we stopped at an English tearoom. There were eight of us from my platoon, and we sat enjoying tea and pastries and talking about the army and girls. This was a great time in my life. Later on, this stop would become a recurring memory for me.

Arriving back at the billets we found everybody busy checking weapons and ammunition. Lieutenant Ryerson, my platoon officer, told me that we were going on a manoeuvre and to be sure to take both smoke and H.E. (high explosive) bombs for the two inch mortar.

I regretted that our stay in Littlehampton was going to be so brief. It was a beautiful town with tearooms, restaurants and of course pubs.

Shortly after lunch, we received an order to be out on the street with all arms and equipment in fifteen minutes. We were hustled into waiting trucks. The tarps were tied down across the back, something we had never done before.

Immediately the trucks moved off, carrying the royals to Portsmouth, where we were driven into the dockyards. The troops then embarked on two troop carriers, the Queen Emma and the Princess Astrid. D and C Companies embarked on the Queen Emma.

Once aboard ship, I was told by one of the sailors that we were headed for Dieppe. Apparently, the raid had been resurrected and it was now called Operation Jubilee.18

In all 237 warships and landing craft set sail for Dieppe on the night of 18/19 August 1942. They carried about 6.100 troops of whom nearly 5,000 were Canadians.

The landing force commander was Major-General John Roberts, the commander of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division.

John Hamilton “Ham” Roberts, Canadian General-Major.19

John Hamilton “Ham” Roberts, Canadian General-Major.19

HMS Calpe was the main HQ ship, from which Major General Roberts commanded the assault force and Captain J Hughes-Hallott, RN, commanded the naval element.

It all seemed rather exciting.

Bognor Regis Observer – Saturday 22 August 1942 Bognor’s Holiday at Home campaign got off to a bad start, it seemed to me. Wednesday’s cricket match, the start of the campaign, had to be abandoned, but truth to tell visitors to the town seemed considerably more interested in gazing out to sea or watching squadrons of Spitfires and other aircraft proceeding at full speed towards the coast of France. Certainly the conversation one overheard was far removed from cricket. Everyone was, of course, speculating on the turn of events at Dieppe. Seawards during the morning those on watch and there were many, were rewarded by a glimpse of a long line of warships steaming slowly along in line ahead, I think that is the correct term. It was a majestic sight. I must admit I became one of the watchers for as long as the ships were in sight. Then during the afternoon there were the sounds of distant (and less distant) gunfire (I presume) which must have proved a distraction from the more prosaic, but less disturbing cricket match. It was not abandoned for this reason, but for others which residents here will know without me mentioning.

The Sphere Saturday 29 August 1942

A scene in the Channel as light naval craft covered the Dieppe Coast.

Bognor Regis Observer – Saturday 22 August 1942 THE DIEPPE COMMANDOS

Come back, come back to Albion at the rising of the sun, come back, come back to Albion from the Victory you have won. At Dieppe from our Channel Port you’ve surely blazed a trail, and with you in the vanguard our Royal Navy sail. Above you fly our air force like giant birds of prey, the Luftwaffe dare not show its face after yesterday. From early morn past sunset the troops come streaming back, they may have suffered losses but of morale there is no lack. Swift vengeance of our Empire looms o’er Hitler’s blackened fame. The South Coast ports of England bid you welcome back again.

Landing craft assembling in Newhaven harbour before the raid.20

Landing craft assembling in Newhaven harbour before the raid.20

Canadian newspaper August 20th 1942

Canadian newspaper August 20th 1942

The Commandos.

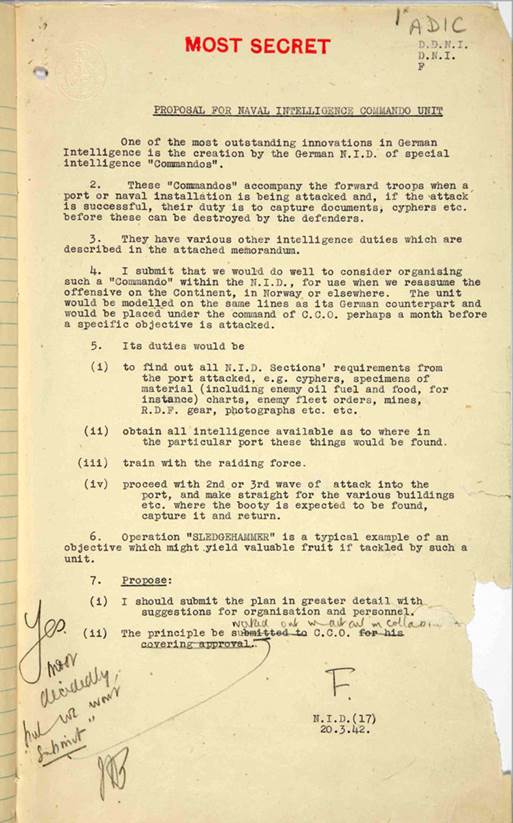

British commandos travelled with the Canadians. In fact the whole mission was devised by them. During the Second World War, Ian Fleming – the author of the James Bond spy series novels – acted as a personal assistant to Britain’s head of naval intelligence, Admiral John Godfrey in the N.I.D – Naval Intelligence Division.

In early 1942 Fleming, along with other naval intelligence specialists, created a team of special commandos that were put into the Dieppe operation under the unit name No. 40 Royal Marine Commandos.

Their primary target was the German headquarters, located at Hotel Moderne near the main harbour in Dieppe. They believed the hotel room housed the Enigma coding machines and a safe with enough material regarding German war operations for the next six to eight months.

BEFORE THE RAID ON DIEPPE ON AGUST 19TH, 1942,

THIS CHINE WAS USED BY 40 COMMANDO ROYAL MARINES

FOR DAILY TRAINING. THE HEADQUARTERS WAS

ESTABLISHED AT UPPER CHINE SCHOOL AND THE

COMMANDO WAS BILLETED IN SHANKLIN, SANDOWN AND

VENTNOR. THE COMMANDO SEQUENTLY TOOK PART IN

THE INVASION OF SICILY AND ITALY AND OPERATIONS

IN YUGOSLAVIA AND THE FINAL DEFEAT OF THE GERMAN

ARMY IN NORTHERN ITALY.

The plan was:

No 3 Commando was to land on Yellow Beach 8 miles from Dieppe and take out the ‘Goebbels’ coastal battery.

No 4 Commando was to land on Orange beach 6 miles from Dieppe and take out the ‘Hess’ battery.

No 10 Commando (linguists) was split into three groups to assist with translation.

No 40 marine Commando was to attack Dieppe harbour directly. On August 18th, the Commando Unit was put on the British ship HMS Locust, whose mission was to breach the inner channel and deliver the Royal Marine Commando into port.

The Canadians would land at blue, red, white or green beaches.

Air Cover

Originally it was thought that aircraft would bomb Dieppe before the soldiers arrived but when it was realised that would cause too much rubble for troops to land, the plan was changed. And instead planes accompanied the boats and carried out strafing attacks.

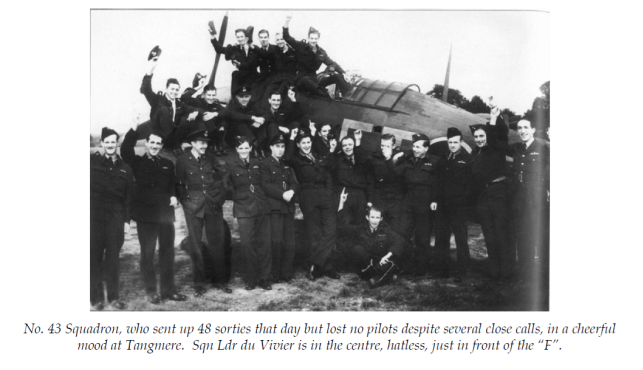

Planes set off from Tangmere and Shoreham.

The first planes to take off were the No 43 Squadron from Tangmere led by Squadron Leader Danny Le Roy du Vivier (a Belgian.). This group of 12 Hurricanes flew to Dieppe and back four times on the morning of August 19th.

Shoreham Airport, being so close to the coastline, suffered several strafing and bombing attacks, and the hangers were damaged. During 1942 the Canadian Army installed a complete airfield destruct system, 60 ft. and 120 ft. pipe mines were strategically placed on a grid system to be electrically detonated in the event of an invasion.25

Hurricanes were temporarily based at Shoreham during ‘Operation Jubilee’.

Aftermath

The German’s were expecting the raid.

Only No 4 Commando achieved their aim. They executed an almost flawless operation, and, in hard fighting, they overran and neutralized the coastal battery on Orange beach. Commando Captain Pat Porteous was awarded the Victoria Cross for his part in this hard-fought battle.

No 3 Commando came under heavy fire managing only to pin down the battery on Yellow beach making it ineffective during the main assault, rather than destroy it.

Fleming’s men were a complete failure. As the first of 40RM Commando landed they came under withering enemy fire and were ordered to re-embark within 10 minutes of landing. Fleming himself did not get off his ship HMS Fernie.

The main assault failed. During 9 hours of fighting, the Allies particularly the Canadian Forces, sustained heavy losses, especially when retreating to join the struggling landing craft.

- 1197 soldiers were killed and nearly 2000 were taken prisoner.

- 34 ships were lost including one destroyer.

- 106 airplanes were lost.

- 28 tanks were destroyed, the second wave having become stuck on the beach

- 48 civilians from the local Dieppe population were killed

| Number set out | Number returned to England | |

|---|---|---|

| Royal Regiment of Canada | 554 | 65 (including 33 wounded) |

| Essex Scottish Regiment | 553 | 52 (including 27 wounded) |

| 14th Tank Battalion | 414 | 247 (including 4 wounded) |

| Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal | 584 | 125 (including 50 wounded) |

| Royal Hamilton Light Infantry | 582 | 217 (including 108 wounded) |

| The South Saskatchewans | 523 | 353 (including 166 wounded) |

| Cameron Highlanders | 503 | 268 (including 103 wounded) |

Canadian dead on Blue beach at Puys. Trapped between the beach and high sea wall (fortified with barbed wire), they made easy targets for MG34 machine guns in a German bunker. The bunker firing slit is visible in the distance, just above the German soldier’s head.27

Canadian dead on Blue beach at Puys. Trapped between the beach and high sea wall (fortified with barbed wire), they made easy targets for MG34 machine guns in a German bunker. The bunker firing slit is visible in the distance, just above the German soldier’s head.27

1,946 Canadians became prisoners of war

British and Canadian prisoners being guarded by German soldiers, Dieppe.28

British and Canadian prisoners being guarded by German soldiers, Dieppe.28

A ward on No 22 Hospital Carrier, formerly the cross-channel boat ISLE OF THANET, at Dieppe. A matron with her orderly is going around the patients in their specially fitted cots.29

A ward on No 22 Hospital Carrier, formerly the cross-channel boat ISLE OF THANET, at Dieppe. A matron with her orderly is going around the patients in their specially fitted cots.29

Commandos returning to Newhaven in their landing craft30

Commandos returning to Newhaven in their landing craft30

Locals remembered their Canadian friends:

We hoped they would be able to do what some of our Commandoes had done before then, that is go in fight the Germans and blow up some important installations and come back without many losses. Instead, we heard they had been pinned down on the beach and mostly all been killed, wounded or captured. We heard, and I don’t know how true it was, that Dave the stretcher bearer was a POW and that Roy had had a hand shot off. I was sad to know that so many likeable men were either dead, wounded or prisoners, and know that they had not been able to give the Jerries the lesson they had hoped to give.

Many of the Canadians had these double-edged knives, oh yes, they used to sit honing them and dragging them across the chin to see if they were sharp enough to shave with. I know they were restless and rather bored. They wanted to have a go at fighting the war. If only they had known what was in store for them.

They came back on hospital trains to Worthing and Newhaven, they had fleets of ambulances and army lorries and took most of the bad cases to Worthing hospital, Swandean and Courtlands hospitals and around the town that had Nissen huts where most of the surgical cases went. There were just hundreds of them, those that didn’t stay went on down the line to different hospitals just shipping them back in and putting them anywhere, wherever they could. A lot of them went all the way to Dover and on to London hospitals, but there were just so many casualties.31

A memorial to the fallen was raised in Telscombe, Peacehaven.

Sussex Agricultural Express – Friday 09 October 1942 A tribute to the memory of those good-hearted Canadian boys, who spent so many happy hours in this hall, and who passed on while fighting for us in the Dieppe raid, August 19th 1942, knowing what ought to be done and doing it at all costs. They were worthy of their country.

This was part of the inscription on a memorial tablet unveiled at Telscombe Hall on Saturday when members of the Canadian units which took part in the raid were represented. Representatives of Britain’s three fighting services and the Home Guard were also present.

The ceremony was arranged by the Telscombe Hall social committee and the memorial was presented by the chairman of the committee Mr E.J. Gollege while Mr Cowley was responsible for the inscription.

Messages were read from the King, the G OC of Canadian forces and Lord Louis Mountbatten.

The Memorial was unveiled by Colonel Unwin Simson, who also read a message from the High Commissioner of Canada (the Hon Vincent Massey) and was dedicated by the Bishop of Lewes (the Rt Rev Hugh M Hordern)

In the course of his address the Bishop of Lewes said that it was one of the greatest honours he had received to be able to take part in that service in memory of those “brave fellows” and he thought the sacrifices they had made were a wonderful incentive to us in England.

Newhaven 2012 Town Council Annual Report.

Newhaven 2012 Town Council Annual Report.

Museum in Dieppe

Museum in Dieppe

— Hilary Greenwood

July 2020

Footnotes

- Wikipedia ⏎

- Littlehampton Through the Wars H.J.F. Thompson 1978 ⏎

- merrynallingham.com > sussex-in-world-war-two ⏎

- MilArt photo archives ⏎

- Wartime Littlehampton Iris Jones 2009 ⏎

- Tales of a Grandfather Alfred H Bowerman 1980 ⏎

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/50/a4392650.shtml ⏎

- Dieppe Derek R Leathers 1994 ⏎

- http://www.wartimememories.co.uk/southeast.html ⏎

- C.E.Nye PAC/DND PA 147108 ⏎

- The Canadian Army 1939-1945 An Official Historical Summary by Colonel C.P. Stacey,1949 ⏎

- The Canadian Army 1939-1945 An Official Historical Summary by Colonel C.P. Stacey 1949 ⏎

- http://www.royalnavyresearcharchive.org.uk ⏎

- http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_dieppe2.html ⏎

- https://maritimearchaeologytrust.org/embarkation-hards ⏎

- The Dieppe Raid: The Story of the Disastrous 1942 Expedition Robin Neillands 2005 ⏎

- www.thememoryproject.com/stories/2437:ron-beal ⏎

- Destined to Survive: A Dieppe Veteran’s Story Jack A Poolton1998 ⏎

- DND/National Archives of Canada ⏎

- Newhaven Local Maritime Museum collection ⏎

- ADM 223/500 ⏎

- Wikipedia ⏎

- Canadian Military History Vol 12 (2003) issue 4 article 6 ⏎

- Tangmere Logbook Summer 2012 ⏎

- Sussex Industrial History no 14 ⏎

- https://www.junobeach.org/?s=dieppe ⏎

- Wikipedia ⏎

- National Army Museum ⏎

- Imperial War Museum ⏎

- Imperial War Museum ⏎

- Dieppe Derek R Leathers 1994 ⏎